Custodial Interrogation and the Legacy of Miranda Rights

Custodial Interrogation and the Legacy of Miranda Rights

Custodial Interrogation and the Legacy of Miranda Rights

By Dr. Michelle Beshears

The landmark ruling in Miranda v. Arizona (1966) forever changed the way police conduct custodial interrogations. Although often thought of as a Fifth Amendment case, Miranda bridges both the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination and the Sixth Amendment right to counsel (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966). The decision ensures that suspects in custody are aware of their rights and protects them from coercive interrogation.

Historical Foundations

Before Miranda, the Court in Malloy v. Hogan (1964) applied the Fifth Amendment’s privilege against self-incrimination to state prosecutions. Around the same time in Escobedo v. Illinois (1964), the Court affirmed that a suspect has the right to consult an attorney during questioning. Together, these precedents set the stage for Miranda by recognizing that silence and the right to counsel are essential safeguards for a suspect’s constitutional rights.

Miranda’s Bright Line and Purpose

Miranda is considered a “bright line” rule that prohibits coercive police conduct while still allowing officers to ask questions (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966). It was not designed to reform policing broadly but instead to prevent compelled confessions by recognizing the psychological disadvantage suspects face during custodial questioning.

Prior to Miranda, courts admitted confessions under a voluntariness test that examined the totality of the circumstances. After Miranda, officers must also demonstrate that suspects were warned of their rights and knowingly waived them before their statements may be admitted (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966).

Required Warnings and Intelligent Waiver

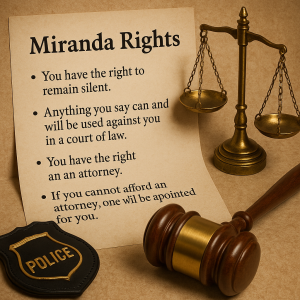

Miranda requires that suspects in custody be told:

-

They have the right to remain silent.

-

Anything they say may be used against them in a court of law.

-

They have the right to an attorney during questioning.

-

If they cannot afford an attorney, one will be appointed (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966).

Officers must then obtain an informed waiver by confirming that the suspect understands these rights and voluntarily chooses to speak.

The Custody and Interrogation Requirement

Miranda protections are triggered only when custody and interrogation coincide.

-

Custody means that a reasonable person would believe they are not free to leave the premises. This includes formal arrest but may also apply in other situations, such as being locked in the back of a patrol car. Routine traffic stops or brief field interviews typically do not qualify as custodial interrogations (Miranda v. Arizona, 1966).

-

Interrogation includes both direct questions and their functional equivalents—words or actions by officers that are reasonably likely to elicit an incriminating response (Rhode Island v. Innis, 1980). Even casual comments designed to provoke a reaction can be considered interrogation.

Doctrinal Exceptions and Appellate Doctrines

Over time, the Court has recognized several exceptions and doctrines that limit Miranda’s scope:

-

Public Safety Exception: Officers may ask about immediate threats, such as the location of a weapon, without warnings (New York v. Quarles, 1984).

-

Booking Questions: Routine questions during booking, such as name or address, do not trigger Miranda (Pennsylvania v. Muniz, 1990).

-

Undercover Interrogation: When suspects speak with undercover officers or informants, Miranda does not apply (Illinois v. Perkins, 1990).

-

Delayed Warnings: If a suspect makes an unwarned statement but later receives warnings and repeats the confession, the second statement may be admissible (Oregon v. Elstad, 1985).

-

Harmless Error and Automatic Reversal: If an improperly admitted confession did not affect the outcome, the conviction may stand (Chapman v. California, 1967). However, when fundamental rights are violated, courts may automatically reverse the sentence.

-

Civil Liability under § 1983: In Vega v. Tekoh (2022), the Court ruled that a failure to provide Miranda warnings does not, by itself, create grounds for a civil rights lawsuit.

Erosion, Adaptation, and Critique

Although Miranda initially demanded precise wording of warnings, later rulings allowed more flexible language as long as the essential rights are conveyed (Duckworth v. Eagan, 1989). Deliberate omissions, however, remain unacceptable.

Scholars continue to debate the effectiveness of Miranda. Some argue exceptions have eroded the decision, while others stress its importance in balancing state power and individual rights. Law review commentary has emphasized that the doctrine remains contested, particularly in light of Vega v. Tekoh and its impact on vulnerable populations such as youth (Langston & Donald, 2017; Eger, 2024).

Conclusion

Miranda rights remain a cornerstone of American criminal procedure, designed to guard against coerced confessions and protect the constitutional rights of suspects. Although narrowed by later rulings, the doctrine continues to symbolize fairness and accountability in the justice system. As courts and law enforcement adapt to new challenges, the balance between interrogation and individual liberty will continue to be a defining issue in U.S. criminal law.

References

-

Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967).

-

Duckworth v. Eagan, 492 U.S. 195 (1989).

-

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U.S. 478 (1964).

-

Eger, J. (2024). The right to remain protected: Upholding youths’ Fifth Amendment rights after Vega v. Tekoh. Virginia Law Review, 110(2), 301–345. https://virginialawreview.org/articles/the-right-to-remain-protected-upholding-youths-fifth-amendment-rights-after-vega-v-tekoh/

-

Illinois v. Perkins, 496 U.S. 292 (1990).

-

Langston, N., & Donald, B. (2017). Fifty years later and Miranda still leaves us with questions. Texas Tech Law Review, 50(1), 1–29. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/faculty-publications/1430/

-

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 (1964).

-

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966). https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/384/436/

-

New York v. Quarles, 467 U.S. 649 (1984).

-

Oregon v. Elstad, 470 U.S. 298 (1985).

-

Pennsylvania v. Muniz, 496 U.S. 582 (1990).

-

Rhode Island v. Innis, 454 U.S. 182 (1980).

About the Author

Dr. Michelle L. Beshears holds undergraduate degrees in social psychology and criminal justice, and graduate degrees in human resource development and criminology from Indiana State University. She served 11 years in the U.S. Army, achieving the rank of Staff Sergeant before commissioning as an officer. Dr. Beshears has led multiple criminal investigations and collaborated with federal and local agencies, including the FBI. She is pursuing a Doctorate in Criminal Justice and serves as an associate professor at American Military University & American Public University. She lives in Clarkridge, Arkansas, with her husband and two children.