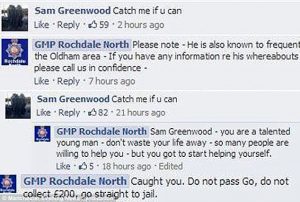

Social Media: Law Enforcement – Catch Me If You Can

By Tonya Schoenbeck

While Facebook has become ubiquitous in most people’s lives, it is also making increasingly frequent appearances in criminal cases. In the past few years, Facebook has emerged as a fertile source of incriminating information from boastful or careless defendants who find Facebook a great way to project their outlaw personas to the world.[1] Does posting information on social media sites allow police officials to seek a probable cause for warrants and arrests, i.e., as a means of bypassing the expectation of privacy as allowed under the Fourth Amendment?

Should this information be protected by the Fifth Amendment right to self-incrimination? This topic is important as our society continues to move through the digital age where pictures and comments can be seen by multiple people (friends) and then shared and shown to the people that have access to their information. It is unreasonable to assume that the same guidelines and rights created prior to the explosion of social media can still apply and allow persons a blanket immunity from repercussion.

To understand what rights are afforded in the age of social media, it is necessary to understand what steps can be taken to minimize one’s information being public. In the majority of profiles on Facebook, the information posted on these walls show some public information. If a party logs onto Facebook, some or all of their information may be able to other users. A party can protect this information by changing their privacy settings to private. Some information is also able for viewing based on a basic Google search of an individual’s name. This does not require you to you log in

Although you choose with whom you share, there may be ways for others to determine information about you. For example, if you hide your birthday so no one can see it on your timeline, but friends post “happy birthday!” on your timeline, people may determine your birthday. When you comment on or “like” someone else’s story, or write on their timeline, that person gets to select the audience. For example, if a friend posts a Public story and you comment on it, your comment will be Public. Often, you can see the audience someone selected for their story before you post a comment; however, the person who posted the story may later change their audience. So, if you comment on a story and the story’s audience changes, the new audience can see your comment.[2] While the privacy settings can be rather confusing, information regarding these settings and how to change them is readily available. A party must also agree to certain terms and conditions, including how their information is displayed when signing up for an account.

With the knowledge of the above, does a user have a reasonable expectation of privacy as afforded in the Fourth Amendment?

The Fourth Amendment states:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be searched.

The Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. What a person knowingly exposes to the public, even in his own home or office, is not a subject of Fourth Amendment protection. But what he seeks to preserve as private, even in an area accessible to the public, may be constitutionally protected.[3] Probable cause and the expectation of privacy are important in relation to social media posts.

What is probable cause? In the criminal arena, probable cause is important in two respects. First, police must possess probable cause before they may search a person or a person’s property, and they must possess it before they may arrest a person. Second, in most criminal cases the court must find that probable cause exists to believe that the defendant committed the crime before the defendant may be prosecuted.[4] To determine when a search takes place, two important need to be considered: (1) whether the presumed search is a product of government action and (2) whether the intrusion violates a person’s reasonable expectation of privacy.[5] Probable cause does exist when a party posts information or photos of them committing crimes online.

A recent case is that of Remel Newson who was arrested for making terrorist threats after a police officer monitoring Facebook saw a post in regards to the George Zimmerman not guilty verdict. This post was public. The censored post reads as:

BLAC N****S CNT GET NO TYPE OF JUSTICE FUCCIN WIT DESE CRACCER’S #KILLALL WHITES DATS DA TYPE OF S**T I’M ON F**K DIS BEEF S**T LET’S KILL COPS ND NEIGHBO RHOOD WATCHER #FACTS DAT

His lawyer, Tasha Lloyd-Garcia, claims her client copied and pasted the “terroristic” post from another person’s profile onto his. She is “disturbed” over how the NYPD obtained a search warrant based solely on the posts. “It doesn’t seem like it would meet the standard for probable cause to get a search warrant,” she told DNAinfo. “There’s no common scheme or plans to carry anything out.” [6]

The right of the people to be secure is the considered their right to an expectation of privacy. This expectation of privacy applies to the location that is subject to the search and/or to the item that was seized. While in most cases, Facebook information is public, or law enforcement has sufficient identifying information about the account to subpoena the company directly, in rare situations a law-enforcement officer might find herself in the peculiar position of believing that incriminating information is posted on a Facebook page, but having no way to get to it without the suspect’s cooperation.[7]

In Katz v. United States 389 U.S. 347 (1967), the Court formulated the “reasonable expectation of privacy” test that is used to decide when a governmental intrusion constitutes a “search” under the Fourth Amendment. The citizen must have had manifested a subjective expectation of privacy and the expectation of privacy is one that society is willing to accept as objectively reasonable. The current expectation of privacy for things posted online is almost non-existent. It is unreasonable to expect privacy on Facebook, even when a profile is private due to the ‘share’ function on Facebook.

Since a party on Facebook does not have an expectation of privacy and probable cause does exist for posts and/or pictures, can the Fifth Amendment right to avoid self-incrimination be used?

The Fifth Amendment states:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.

A feasible argument can be made that these postings are protected by the Fifth Amendment (self-incrimination) and are not enough to create probable cause for searches and warrants. This information can range from pictures to actual postings (words). These pictures and postings have provided probable cause for the arrest and/or search of a person and their home.

The Fifth Amendment’s privilege against self-incrimination has been held to apply not only to statements made by a defendant in open court or in response to government interrogation but also to documents or other information the defendant is ordered to furnish to the government via subpoena. Even if the documents themselves were created without any compulsion from the government, the Supreme Court has held that the Fifth Amendment may protect the act of producing them as having “communicative aspects of its own, wholly aside from the contents of the papers produced.” n38 This “act of production” doctrine and the unstable meaning of what constitutes “testimony” interact with Facebook information in unpredictable ways.[8]

To determine is a party’s Fifth Amendment rights are violated, there are three elements to the alleged violation that must be present. They are i.e., compulsion, incrimination, and testimony. Compulsion requires that law enforcement or another government agent put pressure on the party to commit the offense. This does not exist in the cases researched for this paper; the party’s posted the information on their own accord.

The second requirement of incrimination limits the Fifth Amendment protection to situations “where a witness is asked to incriminate himself – in other words, to give testimony which may possibly expose him to a criminal charge.” The party was not asked to provide testimony, rather they uploaded pictures or posts for their friends and family to see. This information was uploaded or posted prior to the party being charged or questioned in regards to a criminal offense.

The final requirement is the testimony. What is testimony? The Court has defined a compelled act as “testimonial” if it explicitly or implicitly relates a factual assertion or discloses information that involves a compelled use of the suspect’s mind. The Supreme Court wrote in Doe v. the United States, “It is the “extortion of information from the accused,’ the attempt to force him “to disclose the contents of his own mind,’ that implicates the Self-Incrimination Clause.”[9] As stated in the above paragraph, the information was not extorted or coerced from the party; rather they made the posts or posted the pictures of their own will.[10]

There are additional cases dealing with social media and law enforcement using things (posts and/or images) to arrest persons. Cases to watch, in addition to the Newson case, are as follows:

-Thaddeus Matthews. Arrested January 14, 2014, for using the ‘like’ function on Facebook on a status posted by an ex-lover. She filed a complaint and he was arrested for violating a restraining order that she had against him. This case is important to watch to determine the victim’s role in maintaining the defendant as a friend. If Matthews remained as a friend to the victim, who could remove/block him at any time, did she also violate the restraining order? It is feasible to arrest and try a person, not for their post or picture, but for ‘liking’ a status?

-Juvenile Todd. Arrested August 23, 2013 for posting pictures of marijuana plants and a bag of marijuana on Facebook. A concerned citizen notified law enforcement of the posts by the juvenile. He was charged with possession of marijuana and drug paraphernalia. This case is important to watch due to the defendant being a juvenile and the complaint being filed by a “concerned citizen”. Who is the ‘concerned citizen’ and how did they have access to a juvenile’s Facebook profile? Was the information forwarded to the individual or did they see it first-hand? The court will also have to determine the age of majority for posting information online, although not only pictures but words.

-Misty VanHorn. Arrested March of 2013 for sending a private message to another individual in which she wanted to sell her children for money. She was attempting to raise money for her boyfriend’s bail. The receiver of the private message notified authorities and Misty was arrested for child trafficking. She pled guilty to child trafficking and was sentenced to ten years in prison. Although she was sentenced, this case would be valid to go to the Supreme Court to challenge the expectation of privacy since the message was private between parties, similar to an e-mail.

These cases should be watched as one is bound to make it to the Supreme Court and will either a) not be heard, establishing that the decision in Katz is the correct decision and probable cause is met or b) will be heard, creating a precedent for all social media.

Is it possible to use either the Fourth or Fifth Amendment to argue against an arrest and/or conviction based on social media? Yes, it is. However, whether that argument would be successful, is doubtful based on the research completed, case precedent, and quite possibly the terms and conditions that one agrees to when signing up for social media websites. But the usage of social media for arrests is something that the Supreme Court will have to eventually answer.

In conclusion, the usage of information posted on Facebook and other social media sites by the party should be allowed to be used for probable cause as the expectation of privacy does not exist. The expectation of privacy does not exist since both requirements of the test are not met. An argument could be made, that a party that creates a private profile should be allowed to prevent a person from ‘sharing’ their post and pictures (as in the Newson case). The Fifth Amendment also does not apply, as long as the information is not forced or coerced by law enforcement or a government official. If the party is forced to post this information by law enforcement or a government agency, the Fifth Amendment does apply. This information should be kept in mind when posting information online. There is a gray line surrounding social media and the rights afforded to an individual.

About the Author: Currently based in Fayetteville, N.C., Tonya Schoenbeck researches and writes on topics concerning modern society, juveniles, and the Constitution. Her interest in these topics is a result of her time in the foster care system. She holds an Associates Degree of science in paralegal studies from American Military University, a Bachelor of Arts in public affairs from Columbia College and a Masters of Arts in legal studies from American Military University.

Bibliography

Sharing and finding you on Facebook, Facebook Data Use Policy, https://www.facebook.com/about/privacy/your-info-on-fb

Probable Cause, The Free Dictionary, http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/probable+cause

Cavan Sieczkowski, Man Arrested for Facebook Post about George Zimmerman, Huffington Post July 23, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/07/23/man-arrestsed-facebook-post-george-zimmerman_n_3639042.html

Nick Kenney, Radio Host’s Ex-Girlfriend Speaks Up About Arrests, wmctv.com, September 26, 2013, http://www.wmctv.com/story/23541639/radio-hosts-ex-girlfriend-speaks-up-about-arrests

Katz v. United States 389 U.S. 347 (1967)

Alyson Shontell, 7 People Who Were Arrested Because of Something They Wrote on Facebook, Business Insider, July 9, 2013 http://www.businessinsider.com/people-arrested-for-facebook-posts-2013-7?op=1

John L. Worrall, Criminal Procedure: From First Contact to Appeal, (4th ed. 2012)

Catharine Smith, 13 Facebook Posts That Got People Arrested, Huffington Post October 30, 2011, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/30/arrested-over-facebook_n_942487.html#s340548title=Photos_Of_Strangle

Charles Montaldo, People Busted After Posting Crimes on Facebook, About.com, http://crime.about.com/od/Crime_101/tp/People-Busted-After-Posting-Crimes-On-Facebook.htm

Fourth Amendment, Cornell University Law School, http://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution/fourth_amendment

Expectation of Privacy, Cornell University Law School, http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/expectation_of_privacy

Fifth Amendment, Cornell University Law School, http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/fifth_amendment

Probable Cause, Cornell University Law School, http://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/probable_cause

Caren Myers Morrison, The Intersection of Facebook and the Law: Symposium Article: Passwords, Profiles, and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination: Facebook and the Fifth Amendment, 65 Ark. L. Rev. 133 (2012)

Damien Gayle, Radio Host Arrested For Clicking ‘Like’ on Online Status of Woman Who Filed Restraining Order Against Him, Daily Mail January 17, 2014, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2541343/Radio-host-arrested-For-clicking-Like-online-status-woman-filed-restraining-order-against-him.html

Todd Wolford, Father and Son Arrested After Marijuana Facebook Post, WCNC.com August 23, 2013, http://www.wcnc.com/mobile-content/local-news/Father-and-son-arrested-after-marijuana-facebook-post-220851541.html

Misty VanHorn, Oklahoma Mother, Attempted To Sell Her Kids on Facebook For $4,000: Police, HuffingtonPost March 12, 2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/03/12/misty-vanhorn-sell-children-facebook_n_2855887.html

[1] Caren Myers Morrison, The Intersection of Facebook and the Law: Symposium Article: Passwords, Profiles, and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination: Facebook and the Fifth Amendment, 65 Ark. L. Rev. 133 (2012)

[2] Sharing and finding you on Facebook, Facebook Data Use Policy, https://www.facebook.com/about/privacy/your-info-on-fb

[3] Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 351 (1967).

[4] Probable Cause, The Free Dictionary, http://legal-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/probable+cause

[5] John L. Worrall, Criminal Procedure: From First Contact to Appeal, 75 (4th ed. 2012)

[6] Cavan Sieczkowski, Man Arrested For Facebook Post About George Zimmerman, Huffington Post July 23,2013, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/07/23/man-arrestsed-facebook-post-george-zimmerman_n_3639042.html

[7] Caren Myers Morrison, The Intersection of Facebook and the Law: Symposium Article: Passwords, Profiles, and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination: Facebook and the Fifth Amendment, 65 Ark. L. Rev. 133 (2012)

[8] Caren Myers Morrison, The Intersection of Facebook and the Law: Symposium Article: Passwords, Profiles, and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination: Facebook and the Fifth Amendment, 65 Ark. L. Rev. 133 (2012)

[9] Caren Myers Morrison, The Intersection of Facebook and the Law: Symposium Article: Passwords, Profiles, and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination: Facebook and the Fifth Amendment, 65 Ark. L. Rev. 133 (2012)

[10] Liz Hull and Suzannah Hills, ‘Catch me if you can!’ Criminal who taunted police on Facebook just a few hours before he was arrested is jailed for 10 months, Daily Mail August 10, 2013, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2388616/Catch-Criminal-taunted-police-Facebook-just-hours-arrested-jailed-10-months.html